It’s an exciting time to be a 20-something copywriter. The internet platforms where we enjoy a generational edge over our more senior peers are in various states of decline or stagnation. Clients and agencies alike are bracing for impact as the prospect of recession grows less and less theoretical. Our audiences have increasingly little tolerance for our presence in their digital lives. And now, on top of that, The Robots appear to be coming for our jobs.

Over the last year, chatbots and generative AI programs like ChatGPT and MidJourney have given the creative world — long presumed to be high ground against rising tides of job automation — a very rude awakening. Through the magic of so-called “generative AI,” an image that once took a human artist several hours can now be loosely approximated in seconds. A piece of copy that once required thousands of flesh-and-blood keystrokes can now be compiled with just a few. Reactions have been mixed.

Depending on who you ask, “AI” is either another all-hype-no-substance tech fad on par with the most amphetamine-addled crypto scams—or the most significant technological disruption since the invention of the atomic bomb. Wherever you land on that spectrum, one thing is certain: it is a subject that lends itself to over-hype. Sharing a name with one of the most compelling and well-explored concepts in speculative fiction doesn’t help.

As we all wrestle with what this technology means for the future, it’s worth examining where it all started, the strange underlying quirks of human psychology that make it feel so real, the ethical grey areas of how it’s made, and the immediate implications and applications it may have for our work.

What It Is: From ELIZA to Siri

Like any good piece of horrifying sci-fi technology, the story of modern AI begins in Greater Boston. In 1964, MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum started writing a computer program to demonstrate the inherent superficiality of human-machine communication. Two years later, ELIZA was born.

The program’s design was simple but revolutionary. When a user submitted a message, it would scan for keywords and use them to formulate a response. This made ELIZA the first computer program capable of simulating conversation—in other words, a chatbot.

A longtime skeptic of “true” artificial intelligence, Weizenbaum understood the limitations of ELIZA better than anyone. He designed its most famous “script,” DOCTOR, as a parody of Rogerian talk therapy (where a therapist often repeats a patient’s words back to them in the form of a question). While the program was impressive for its time, its creator knew it didn’t truly understand anything typed into it. For him, that was the point.

Unfortunately, when Weizenbaum shared his creation with others, it was a hit for all the wrong reasons. Many early users became convinced that ELIZA was sentient. When the professor’s secretary tried it, she famously asked him to leave the room so she and the program could have a “real” conversation. For Weizenbaum, this was profoundly unsettling.

"I had not realized ... that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people."

Chatbots have come a long way since ELIZA, from instant-messaging sites like Cleverbot in the 2000s to voice-activated “virtual assistants” like Siri in the 2010s to contemporary large language models like Bing, Bard, and ChatGPT—but Weizenbaum’s initial skepticism has yet to be proven wrong. Even ELIZA’s slickest descendants still lack an intuitive understanding of the information they process, and none have anything close to true artificial intelligence. For now, sci-fi overtones and breathless press coverage aside, “AI” is only as real as we think it is. That may not be as reassuring as it sounds.

How It Works: The ELIZA Effect and Good Old-Fashioned Stealing

Joseph Weizenbaum wasn’t just the father of modern chatbots. He was also among the first to recognize the psychological phenomenon that makes them so uncanny: “The ELIZA Effect.”

In the broadest sense, the ELIZA Effect is the human tendency to anthropomorphize the actions of machines: "read[ing] far more understanding than is warranted into strings of symbols—especially words—strung together by computers.”

From a recent research paper on the dangers and ethical implications of large language models:

Our human understanding of coherence derives from our ability to recognize interlocutors’ beliefs and intentions within context. That is, human language use takes place between individuals who share common ground and are mutually aware of that sharing (and its extent), who have communicative intents which they use language to convey, and who model each others’ mental states as they communicate. As such, human communication relies on the interpretation of implicit meaning conveyed between individuals. The fact that human-human communication is a jointly constructed activity is most clearly true in co-situated spoken or signed communication, but we use the same facilities for producing language that is intended for audiences not co-present with us (readers, listeners, watchers at a distance in time or space) and in interpreting such language when we encounter it. It must follow that even when we don’t know the person who generated the language we are interpreting, we build a partial model of who they are and what common ground we think they share with us, and use this in interpreting their words.

Text generated by an [AI program] is not grounded in communicative intent, any model of the world, or any model of the reader’s state of mind. It can’t have been, because the training data never included sharing thoughts with a listener, nor does the machine have the ability to do that. This can seem counter-intuitive given the increasingly fluent qualities of automatically generated text, but we have to account for the fact that our perception of natural language text, regardless of how it was generated, is mediated by our own linguistic competence and our predisposition to interpret communicative acts as conveying coherent meaning and intent, whether or not they do. The problem is, if one side of the communication does not have meaning, then the comprehension of the implicit meaning is an illusion arising from our singular human understanding of language (independent of the model). Contrary to how it may seem when we observe its output, an [AI program] is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot.

-“On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots,” Section 6.1

Humans mostly use language to communicate with other humans—for most of human history, that’s been the only way to do it. When we encounter a piece of text, we tend to assume it’s the work of another sentient being. We understand it by recognizing its context, intentions, and perspectives—and in doing so, we project humanity onto it. But when that piece of text is not the product of another sentient being, things can get wacky.

The ELIZA Effect helped sell Joseph Weizenbaum’s colleagues on the sentience of his pioneering chatbot in the 60s, and it’s already helping to sell a lot of journalists and researchers on the sentience of large language models today. In some ways, this is harmless and funny. In other, more meaningful ways, it’s not. Many prominent AI ethicists argue that the phenomenon can amplify the already alarming capabilities of programs like ChatGPT to spread misinformation, harmful biases, and hate speech.

If these programs had any capacity to intuit meaning from the information and content they process, this might be marginally less dangerous. Unfortunately, without comprehensive human oversight and moderation, they effectively regurgitate everything they consume with no ability to discern fact from fiction — let alone right from wrong. With companies like Google banking on a future where talking to LLMs replaces searching the web, that creates a lot of cause for alarm.

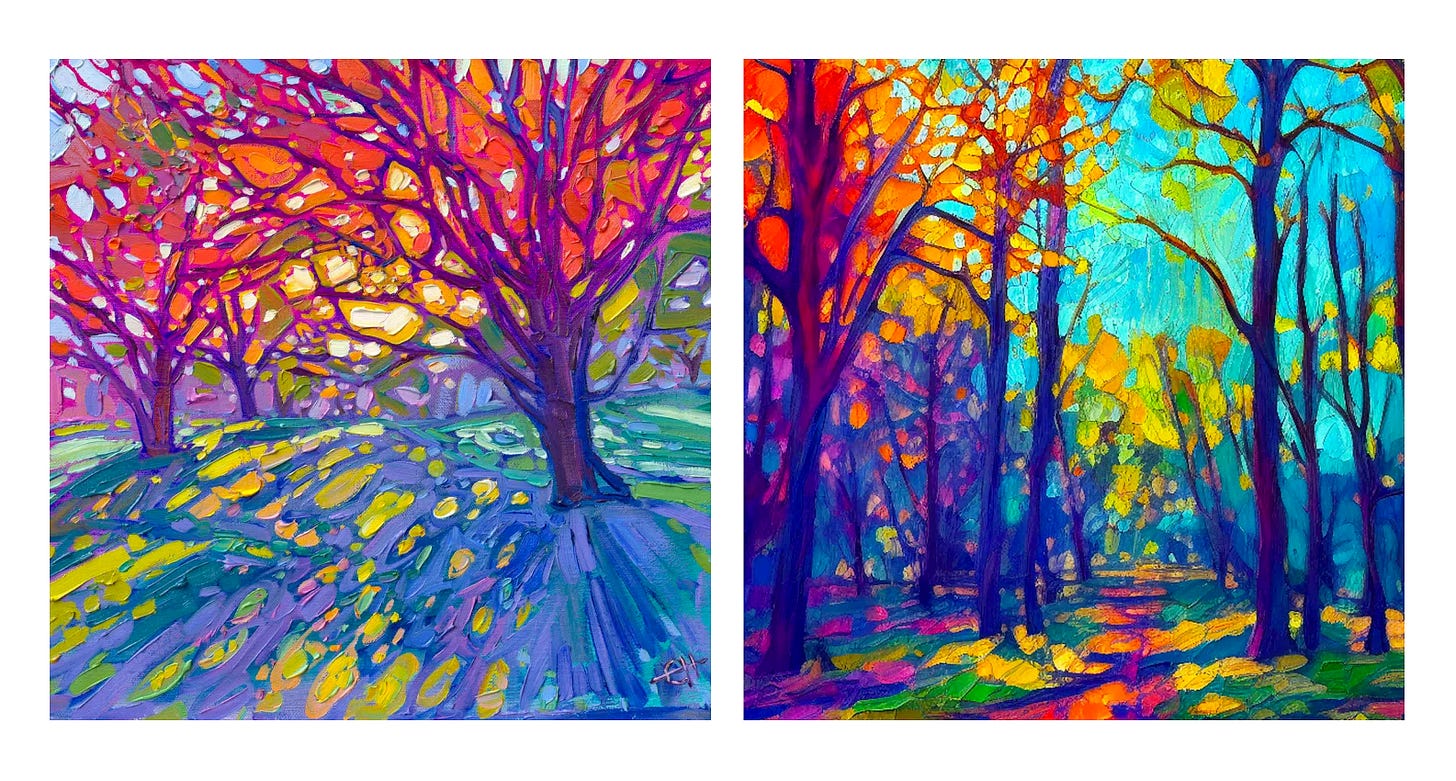

The ethical gray areas surrounding “AI” don’t stop there, either. For a program like ChatGPT to reach a state where it can generate content based on prompts from a human user, it first needs to be trained on billions of pieces of existing, human-generated content. In classic “move fast and break things” style, most current AI startups are opting to carry out this training without the consent of a single human creator. Now, as Silicon Valley and Wall Street rush to anoint a new set of multi-billion-dollar unicorns, many creators are discovering that programs trained on their work without their consent have become eerily capable of emulating it. With all of that in mind, serious questions linger about how the human creators who really built these programs (and the underpaid moderators tasked with papering over their shortcomings and flaws) should be compensated.

What It Means For Us: Let the Robots Take (Some Of) Your Job

This is where I admit that I’ve been using ChatGPT at work for the last several months. Ethics and raison d'etre aside, it’s a fun (if still somewhat limited) new tool for brainstorming and copy development. It’s like having constant access to a room full of drunk toddlers who have read every book ever written—not a true 1:1 creative partner, but an interesting source of noise and occasional coherence. I don’t see it automating me out of my health insurance any time soon, but I’m trying to get good at talking to it while I can.

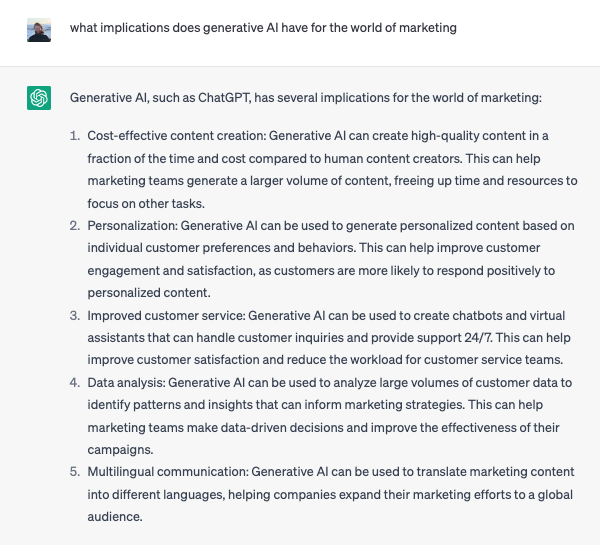

In the long term, it’s hard to say how “AI” might reshape the marketing world.

In the short term, it already has the potential to be a useful tool for increasing productivity—but don’t overestimate it. Until the legal, ethical, and technical concerns associated with “AI” are addressed, the best way for marketers to use programs like ChatGPT is with caution. Most successful AI-powered marketing is still internal-facing or subject to rigorous human revision before going external, and that seems unlikely to change soon. Trusting a chatbot to speak or create on your behalf without safeguards remains a very risky move.

2023 may be the year “AI” went from high-concept fantasy to inescapable reality, but how it evolves from here will depend on how we use it.

Good Example: On the heels of last year’s “Draw Ketchup” campaign, where thousands of people worldwide were invited to draw a ketchup bottle and returned thousands of predictably Heinz-shaped drawings, the brand ran the same experiment through DALL-E with similar results. Fun, clever, and subject to healthy quantities of human input.

Bad Example: CNET began using an “internally designed AI engine” (editor’s note: “uh huh, sure.”) to compose articles last November. Following numerous incidences of factual errors and plagiarism found in the site’s AI-generated articles, the program was paused in January. Embrace half-baked content generation systems with no oversight, get half-baked content.